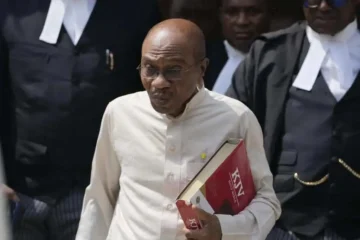

Former military governor of Niger State, Col Lawan Gwadabe (rtd), speaks to our correspondents on why he had not said anything about Major Gideon Orkar coup of 1990, which attempted to overthrow the regime of military president, Ibrahim Babangida. He says he’s offering to speak on the matter now to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the putsch and to address some of the misconceptions about the coup.

You have not been talking since your release from detention. Why?

Well, I made a promise to myself while in prison that the only time I would speak publicly would be right in front of the prison after my release. I vowed to stay out of circulation, and honestly, it’s been for my own good.

It’s perfectly fine to explore other aspects of life. After spending so many years in the limelight, I believe there comes a time when, as they say, when the beat changes, the dance must change too. So, I made a conscious decision to stay away and live more privately.

I still attend events occasionally. For example, I served as the Chairman of the Nigerian Road Safety Commission for over two years, so I wasn’t completely out of sight.

But as for constantly granting interviews and mingling here and there—I think I’ve had my fair share of that. Now, I prefer to keep things calm and maintain my peace.

You’re not the only one, some of your seniors in the military like Idiagbon followed similar patterns, is this a military tradition?

No, it’s not a tradition. It’s just a personal choice—a kind of individual idiosyncrasy. That’s all. I have my own reasons, and I’ve chosen to keep them personal. My requirements are very minimal, so I decided to just stay where God has kept me for now.

Having held numerous administrative positions, you could have made significant contributions when Nigeria transitioned to civilian rule. Don’t you feel any guilt about not playing a more visible role in that process?

Well, you might be surprised. What you are seeing here (pointing at the numerous files on his table) are, in fact, contributions—first to Obasanjo’s administration, and later to Jonathan’s government. We were also active during Yar’adua’s time. He actually referred to me as his senior brother, because I had worked closely with General Shehu Musa Yar’adua in Lagos. So we had that bond. I’ve been doing my best. I’m just not someone who seeks the spotlight anymore. I used to be, yes—but those days are behind me. We’ve contributed a great deal.

In terms of national security, there’s hardly anything we haven’t been involved in. If you need specifics, I could provide plenty. And let me be clear: when President Yar’adua said he didn’t fully understand the Niger Delta issue or aspects of foreign policy, he turned to me.

I did my best to guide him, drawing from my own experience. In fact, the last memo I wrote to him helped him grasp the complexities of the Niger Delta. That ultimately led to the creation of the Niger Delta Ministry—which was my recommendation.

So, I may be quiet publicly, but I’ve never stopped contributing behind the scenes. My involvement with those in power has been steady for the past twenty-something years.

Let’s talk about the 1990 coup. At the time, you were still in active service and serving as the governor of Niger State. By April 22, it will be 35 years since that coup attempt. From accounts of several actors, you played a significant role in foiling it. Can you share your recollections of that watershed moment in Nigeria’s history?

Don’t forget, I was a military governor then and if the Nigerian government were to fall, we’d all be gone. So, in a sense, it was also an act of self-preservation. We had to stay informed and take an active role.

I got involved early on because I had intelligence about their plans as far back as February 1990. We infiltrated the system. As a governor, I had extensive contacts across the country, and my intelligence sources were broad and effective.

Whenever I came across any potential threat to national security, I would compile a detailed report and send it to the president and the relevant security authorities. That was part of our training. That was the job.

Once I uncovered this particular plot, I began writing briefs regularly. Then I learned that Major Gideon Gwaza Orkar had been recruited into it. Orkar was a good officer—I knew him well. He served under me when I was at the Directorate of Armour in Lagos. And whenever he came to Lagos for meetings while stationed in Shaki, he would stay at my house.

We had a strong connection. He had also met me at the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA)—he was a cadet when I was about to graduate, so I was his senior. Later, he joined the Armoured Corps, where I served. So, I knew him as a bright young officer.

When I found out about his involvement, I felt he was being used as a kind of conduit for the Niger Delta agitators. So, I asked his commandant if, in the interest of national security, he could allow Orkar to meet with me. I wanted to send him to the president directly.

The commandant agreed, saying they weren’t in the middle of training at the time. So, Orkar was sent to me.

I told him, “Gideon, you know I have vast information about what’s happening.” He acknowledged that. I said, “There are pockets of agitations across the country. At our last caucus meeting, we briefed our seniors, and they’ve been factoring this into their decision-making.”

For example, the establishment of OMPADEC was part of efforts to address grievances in the Niger Delta. With the 13% derivation that was eventually granted, the region received substantial resources to accelerate development. But has that really happened?

Not quite.

Agitating officers in the Niger Delta hadn’t aligned with their leaders to understand what the federal government was doing—or failing to do. There was a disconnect. And yes, there was radicalism in their thinking. Emotional responses can cloud rational judgment. So, while the claims of marginalisation had merit, the government was working on interventions.

I told Orkar, “Look, when they mention the Middle Belt—it’s just an aphorism. The Middle Belt is in Nigeria. Are you a Middle Belt officer?”

He replied, “No, sir. I’m a Nigerian officer.”

“Good,” I said. “So why are they trying to bring you into this? I don’t want to know what they’re telling you—but I’m giving you a chance, as one of us, to lay everything on the table with the president. Not to arrest them—but to disarm them. Let the government talk with them and understand their frustrations.”

That was my intention.

He responded, “Whatever you ask me to do, sir, I will do.”

I reminded him, “If you’d done anything wrong, I could’ve had you arrested right here. But I didn’t. So go to the president and speak the truth about everything you know.”

He mentioned that his car wasn’t in good condition, and I told him not to worry. I called my ADC and Director-General of Government House. I said, “Orkar is your guest. He needs new tyres.”

The Niger State Supply Company provided four new tires for his car. The DG Government House gave him N20,000—quite a large amount back then—and he headed to Lagos.

To his credit, he left very early the next morning. I don’t recall the exact date, but it was a Wednesday in March. By 2 p.m., UK Bello called me and said, “Sir, the officer is here.”

I told him, “UK Bello, I beg you in the name of Almighty God, whatever the president is doing, he must see Orkar today.”

He said, “Consider it done, sir.” I had already phoned the president that morning to let him know Orkar was on his way.

Orkar sat in the ADC’s office until 6 p.m., there had been a Federal Executive Council meeting, which ran long. When the president returned and saw Orkar, he said, “Gideon, your boss told me you were coming. Okay, I’ve seen you, but I’m tired. Can you come back tomorrow?”

And that was it.

Orkar bantered a bit with UK Bello and left. But realistically, it’s likely he had already informed his co-conspirators and they were nearby in Lagos, awaiting the outcome of that meeting.

When that meeting didn’t happen, I believe it rattled them. They probably assumed their secret plan had been discovered; how else could we have known so much? So I believe they panicked, changed their timeline, and launched the coup earlier than planned.

That’s why it didn’t succeed as they had envisioned.

Do you think, former President Babangida could have been aware of their plans? Could that be why he didn’t meet with Gideon Orkar that day?

No, I don’t think so. Whatever he knew about the situation came from the information we were providing him. But I felt that once the plot reached a certain stage, it was time for Orkar to brief him directly—so the government could step in, disarm the agitators, and allow things to return to normal.

Nobody was interested in arresting anyone. If they had genuine grievances, fine, what are those grievances? If the authorities felt it was necessary, they could sit down and listen. At that point, the whole thing was still in its embryonic stage.

When Orkar couldn’t see the president, did he reach out to you?

No, he didn’t get back to me.

Did you reach out to him?

No, I didn’t.

But UK Bello informed you that the president couldn’t see him?

Yes, he told me. But I also told UK Bello that it was a mistake. Still, it wasn’t my call to make at that point. They should have followed up. They didn’t.

I was a military governor. I had my own responsibilities and I was focused on doing my job.

The focus seemed to be Lagos. But from what we’ve gathered, it seems you coordinated the whole operation from Niger State. How was that?

Well, I was the governor of Niger State at the time. I couldn’t just leave for Lagos.

So, I did what I could from where I was. When telephone lines were working, communication became key. We knew Lagos was the main target. If they had gotten to Dodan Barracks and harmed the president, you can only imagine what the consequences would have been.

The goal was to alert anyone who could act, to get the word out quickly. Keep in mind, this was happening at night. Most people were asleep. Many didn’t even know what was going on.

We had a sense that something was coming, but we didn’t know exactly when. When it finally unfolded, it became clear: this was their game plan.

The best course of action was to coordinate with loyal officers and disarm the plotters. And that’s exactly what we did.

You mentioned elsewhere that it was the Director-General, Government House, who alerted you to the movement of some military trucks. Is that correct?

No, no, no—you didn’t read that part very well.

It wasn’t the DG himself who first noticed anything. He was called by a friend of his in Lagos—someone living in Surulere—who had seen tanks moving across the bridge at night. That was highly unusual.

So the friend, who’s also from Niger State and had the president’s best interest at heart, called the DG and said, “Look, I think something is wrong.”

Once the DG got the call, he immediately contacted me. By then, we had already gathered at the Government House.

And then, the duty officer from 242 Recce Battalion in Ikeja also called me. He said, “Sir, I’ve noticed two officers have taken tanks out of the Cantonment.”

I asked, “How can they take tanks out? Where is the Commanding Officer? What are you people doing moving tanks at night? Is there some kind of emergency in Lagos?”

He replied, “No, sir.”

And I said, “Then there’s a problem. Stay on standby. We’ll get back to you.”

At that point, I realised we couldn’t just sit still and watch. If we didn’t act, anything could happen in Lagos. So I decided we had to take charge from here—from Niger.

That was entirely my personal initiative.

My name was number two on the list to be assassinated—I knew that. I knew everything that was at stake. And that’s why I said: we must fight this.

A lot of those details didn’t make it into the original reports, but now you’re hearing the full story.

They included your name after Orkar opened up to you?

No. My name was included from the planning stages. Now you understand why we stood down?

And you knew all that even at that stage?

Of course.

So why didn’t you arrest Orkar after he opened up?

Why would you arrest them at the planning stage? If you arrest Orkar, what would you tell him? You don’t have the evidence—just an inclination that, yes, this man is meeting, saying, “Let’s do this, let’s do that.” But there was no agreement at that stage.

They were just developing their plan. So, if you arrest somebody at that point, what concrete justification would you have?

With the benefit of hindsight, one might say that the Orkar coup was more like a civilian-led effort given the role of Ogboru with collaboration with some retired military officers.

The young officers involved were all serving officers with their own troops. But yes, they also recruited ex-servicemen from the Niger Delta. And the financier was Great Ogboru.

It’s true they met at his fishing company’s warehouse—but that was also a kind of deception. They couldn’t have used civilians to storm Dodan Barracks. What would civilians know? For example, those who sabotaged the tanks in Dodan Barracks that UK Bello and his team were to use—they couldn’t have been civilians.

They must have been serving soldiers, moving in and out of duty. So I’d say there’s some inaccuracy in that version. It was a combination of retired soldiers and active-duty officers.

There have been various accounts of how the coup was foiled. Everyone has told their story. Can you take us through your own role?

No, I wasn’t directly active. I was indirectly involved because I wasn’t in Lagos. My role was to give instructions to the senior officer we had designated to take charge of operations. Whatever details followed after that; we weren’t privy to them.

But we knew they marched to the radio station, assaulted the place, and stopped the broadcast after making arrests. That was what I was interested in.

The following day, I was briefing the Chief of Army Staff so they could understand our initiative—what we were doing—while they responded in Lagos with the information we provided.

So yes, there are many versions of what happened on the ground that night in Lagos. I wasn’t there. What I know is what I’v written.

Would you say it was a failure of intelligence?

Yes, definitely.

General Bamaiyi in his book said the heads of DMI, Naval, and Air Intelligence should have been arrested after the coup failed, do you agree?

That’s their politics. I’m not interested in that. My only goal was to direct what needed to be done to save the president and the government. That’s all.

There are conflicting accounts of how IBB was saved from Dodan Barracks. Some say he escaped through a tunnel.

There is no tunnel in Dodan Barracks. Forget that. No tunnel.

So, from your recollection, how did it happen?

I wasn’t there. What I was told is that he was watching television when they came and literally whisked him away for his own safety.

There’s a procedure in case of any infraction within the presidency. The officers on duty are trained to take specific actions. It’s called standard operating procedure.

There’s also a designated location where the president must be taken once evacuated. And they followed the procedure. That’s all.

I wasn’t on the ground, and to be honest, when I came back from Minna to pick up the corpse of UK Bello, I wasn’t in a good frame of mind.

How did UK Bello die?

He saw the officers and recognised one—his course mate, Lt. Colonel Anthony Nyiam.

He said, “Anthony Nyiam, all of you—we are all colleagues now. We can discuss our differences.”

Nyam, in fairness to him, was hesitant. But Major Saliba Mukoro —the actual active agitator—said, “No, there’s no need to talk to UK Bello.”

Then he and another officer just opened fire and killed UK Bello on the spot.

WO2 Yusuf, who had earlier discovered that they had removed the firing pin from a tank, was watching from a distance. Once they killed UK Bello, he jumped out. But what could he do? Nothing.

He tried to run. They shot him in the leg. The adrenaline kept him going.

He ran through the cemetery and eventually fell into the compound of a police sergeant. The sergeant’s family took him to the hospital the next morning. His leg was shattered. But he survived. He’s still alive today.

Do you recall the role played by others in other parts of the county like General Hassan Katsina?

Yeah, General Hassan was very, very tough. He said, “No, this nonsense must stop.” He, himself, rallied down all the officers.

But the best thing he did was to just act. He retired as former Chief of Army Staff—see how patriotic he was. It was very touching for General Hassan, at that age, to say, “Let’s go,” to take the radio, take the manager of LRC, and head to the studio.

In a very skimpy dress, he went, made a broadcast, and said, “Put it on.” You know. There are others who played active roles in foiling the coup.

Many believe that the coup failed because of that early broadcast by Orkar which excised some parts of the country.

Yeah, that alienated them completely.

For example, Orkar, in his speech said: “We wish to emphasise that this is not just another coup, but a well-conceived and executed one for the marginalised, oppressed, and enslaved people of the Middle Belt and the South.” Then he proceeded to excise five northern states. So, is that a patriotic action? That kind of statement completely angered virtually everybody.

And everybody realised that, well, these characters were not serious. And secondly, they’re not patriotic—neither were they nationalistic. So everybody rose against that nonsense.

I call it Orkar’s April Fool version. Unfortunately, it came on the 22nd, not the 1st.

There is a popular belief that Abacha played a very significant role in foiling the coup…

I’ve given you the account I know, Abacha’s part is there, it’s written. What the senior officers did after that, I’m not privy to.

Abacha himself was fighting for his own survival. If his son hadn’t taken him back to his house, those two young officers who went to look for him had gone back again. So, he was lucky.

And once I found out he was at home, I said, “Okay, sir, we’ll keep engaging with you. But this is what we’re doing on our own.” Remember, it was night.

This whole thing started at 11 p.m., and we didn’t finish until about 8 a.m. Nobody even went to ease himself. We were just sitting there, working the phones.

You may not understand the scenario. It was not an easy thing. It was really not an easy thing.

You served under Generals Buhari, Babangida, and Abacha—three very different military rulers with distinct legacies. What were your personal experiences working with each of them, and how would you compare their leadership styles and vision for Nigeria?

It’s all written in my book—copiously. It’s like a song. My relationship with everyone, you’ll read it there. I hope Daily Trust will be part of the production of the book.

A lot of people want to know what you knew about June 12.

I know.

Especially with the account from General IBB.

Correct.

Should Nigerians expect a different narrative?

June 12 is a watershed in Nigeria—everybody knows that. I’ve been privileged to serve on two committees that sat down to write recommendations on June 12.

And I’ll stop at that. The recommendations are there. You’ll read about them when the book is finished.

Are you concerned that your role in foiling the Orkar coup was not specifically credited in General IBB’s book?

Well, I’m just in the process of reading Babangida’s book, to be honest. Okay? So, I’m sure an interview with him will give you insight into why he didn’t mention our names—or if he felt we didn’t do anything.

We’re not bearing any grudge. He’s our boss. And whatever he does, we believe he’s right.

You were close to four former Heads of State, including former President Olusegun Obasanjo, since you were both implicated in the same coup. He later became president, which suggests you had some sort of relationship with him. Why didn’t you use that to your advantage?

I think Obasanjo should answer that question. He should answer it. In my book, you’ll see how we suffered together. We were in the same room. Let me give you a snippet: when they threw us into detention, we were sleeping on the bare floor. The DMI then, Brigadier Sabo, was my coursemate, so I sent for him. I said, “I want to write a letter to General Sani Abacha. You’re the DMI, so you take it to him.

He brought me a sheet of paper, and I wrote to Abacha: This thing you’re doing is wrong. You, yourself, in your heart, you know there was no coup. So don’t treat these people like this. I said, For me, I don’t care. I can sleep on the floor. But not the former Head of State. We should be careful about where we find ourselves tomorrow.

Three days later, General Sabo came back from Abuja with a vehicle loaded with beds, mosquito nets, and so on—for the place where we were being detained. So that’s just one example. Obasanjo and I are not enemies. We are friends.

Did he appreciate that friendship?

You know him better than I do. All of you know him very well.

Perhaps you didn’t reach out to him after you all regained freedom…

We’ll leave that for later. When the time comes.

The general impression most people have of Abacha is that of a ruthless leader. However, some who defend his legacy say he was the only Head of State who pardoned individuals who plotted coups against him. Given that you were also affected, what’s your impression of him?

You’re trying to veer into the 1995 coup, and I will not answer any question on that. I will not. No, I will not. Because if we start on that, we’ll be here till tomorrow. Alright?

Even in that matter, the role I played—you’d be very impressed. So let’s just leave it at that. I didn’t commit any offence. I had 7,000 officers and soldiers under my brigade, and I was the only one arrested. In fact, I wasn’t even arrested. I was invited for a meeting in Jos, based on the fact that we used to send reports on Bakassi and Cameroon every two weeks to the Head of State. Okay. And your townsman was my Brigade Intelligence Officer—Major Oku. So I told Oku, “Bring all the Bakassi documentation, and let’s go for the meeting.” Now tell me, if I were planning a coup, would I do that?

But 35 years later, the agitations that led to the failed coup still persist in one form or another.

Correct.

Do you think Nigeria has learnt any lessons?

Well, maybe yes, maybe no. I don’t want to delve too deeply into that, because I’m writing a book.

I’ll save my thoughts and observations on the military interregnum and civilian governance for the conclusion of my treatise in the book.

Earlier, you told us about the role you played during the Yar’adua episode. Do you think things have improved since then, or are we still building on your suggestions?

You know, the Niger Delta is a very complicated enterprise. And no matter what the federal government has done—military or civilian—there’s been a lot of misapplication of funds.

By now, with the kind of money that has gone to the Niger Delta—from the time of OMPADEC to the creation of the Niger Delta Ministry—that region should be looking like Dubai.

But why is there still no infrastructure? Why has there been no investigation or prosecution concerning the massive amount of money siphoned from that place? Why is there still illegal oil bunkering and industrial-scale theft of our patrimony—crude oil? Why?

Someone said, ‘anybody who hears the name Gwadabe will think coup’. There were reports that you’ve been part of coup plotting since 1975. Were you implicated simply because your name strikes fear?

We’re here to discuss the Orkar coup, so let’s leave it at that. When the time comes for us to discuss all the other matters, I promise you, I’ll give you the privilege of being the first to know what I’ve written. I have tons of material, and I’m sure it’s not going to be just one book.

*Culled from Daily Trust.