(As published in Sunday New Telegraph on 8th February, 2026)

By SHEDDY OZOENE

The next time Nigerians reflect on the country’s deeply flawed elections and the persistent ineptitude of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), it may be worth pausing to interrogate not only the electoral umpire, but also the role played by civil society and democracy advocates. Today, more than at any other time in our history, their influence on the electoral system, and their own accountability, has come into question.

On this issue, I use YIAGA AFRICA as a sampler, chiefly because it has played perhaps the most visible role in election advocacy and in managing public expectations around recent polls.

Founded in 2007 as a student organisation at the University of Jos, YIAGA AFRICA has grown into one of the most prominent civil society voices in Nigeria’s electoral space. It presents itself as a democracy and human rights organisation committed to election integrity, civic participation, and the strengthening of democratic institutions. At a time when Nigerians were beginning to lose interest in elections, the organisation played a major role in advocating public participation in the electoral process.

On paper, that mandate is noble. In practice, however—particularly when one considers its activities over the past few years—there is a troubling pattern in its public engagement that deserves closer scrutiny.

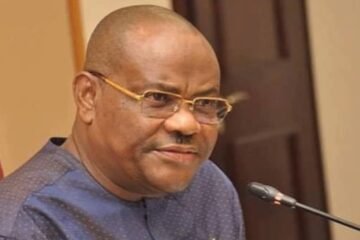

In the build-up to elections, YIAGA AFRICA – especially through its Executive Director, Mr. Samson Itodo – often becomes more visible in the media, sometimes even more visible than INEC Public Affairs Officials. From one television platform to a radio station and various other media, Itodo and his officials saturate the space with their commentaries: interpreting the Electoral Act, explaining INEC guidelines, urging citizens to trust the process, assuring Nigerians of INEC’s preparedness, and reinforcing confidence in electoral technologies supposedly designed to guarantee transparency.

This trend was especially pronounced during the 2019 and 2023 general elections. Long before polling day, Nigerians were repeatedly assured that the process was sound, that the systems were “rock-solid,” and that the elections would reflect the will of the people.

We all know how that turned out.

Both elections fell disastrously short of expectations, with the last one producing what many Nigerians still regard as one of the most brazen electoral heists in the country’s history. Even before the now-infamous “glitch” was announced, the process was visibly flawed and failed to meet basic democratic standards.

No one expects YIAGA AFRICA or its leadership to man polling units or conduct elections on behalf of INEC. But it is equally important to say this: it is not their place to offer assurances about outcomes they neither control nor can guarantee.

Yet, when public anger peaked and demands for accountability grew louder after the elections, YIAGA AFRICA and its leading voices simply vanished from the airwaves. The confidence, clarity, and moral urgency that characterised the pre-election period suddenly evaporated.

Now, as Nigeria edges toward another round of elections, the pattern appears to be repeating itself. YIAGA AFRICA is quietly re-emerging. Recently, Samson Itodo weighed in on national television following the Senate’s rejection of electronic transmission of results to the INEC IReV portal. Its his right as a citizens even if we know it is an effort in building public confidence. Once again, the organisation is positioning itself as a key interpreter—and gatekeeper—of the electoral conversation.

This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question: is this becoming a cycle?

As Nigerians brace for another election cycle, we must ask whether we are being led down the same road—with the same voices, and perhaps, ultimately, the same disappointing destination.

Most of Nigeria’s elections have fallen short, sometimes due to human error, often because of deliberate compromise. That history explains the deep scepticism with which Nigerians now approach the ballot. So when a group—however credible—consistently steps forward before elections to seize the public space and reassure citizens about a process it does not control, it is only reasonable to ask hard questions, especially when the pattern has repeated itself with similar outcomes.

This brings us to the more critical issue: accountability.

Every society needs organisations like YIAGA AFRICA. Democracy advocates play an important role. My concern, however, is how much the organisation has come to occupy a space that properly belongs to INEC. In the last general election, much of the confidence Nigerians carried into polling day did not come from INEC’s own clarity or institutional credibility, but from interpretations and assurances offered by civil society groups—YIAGA AFRICA in particular.

With a presence, by its own account, in all 36 states, the FCT, and all 774 local government areas, one would expect detailed post-election reports and sustained engagement long after voting ended. Instead, what followed was largely silence. Now that those voices are returning, the pattern raises legitimate questions—not about YIAGA AFRICA’s relevance or right to exist, but about purpose and accountability.

Civil society organisations are meant to speak truth to power, not serve as advance public relations buffers for institutions that routinely fail the people. If YIAGA AFRICA is truly independent, its accountability should not end on election day.

While the organisation deserves credit for civic education, it must step up its citizen watchdog role—calling out failures, negligence, and manipulation before, during, and after elections. It must be willing to speak uncomfortable truths, even when doing so costs access. It must stand with citizens and refuse to trade credibility for proximity to power.

When advocacy drifts into perception management, it risks becoming legitimisation. Silence after failure is not neutrality. And at that point, some of us may be justified in suspecting complicity.